Design and gender: perception of yesterday and today

Théa Lefeuvre, Bertille Porcq, Chloé Lepeintre and Clara Diez from DNMADE questioned gender issues in the design of yesterday and today. How has design played, and still plays, a crucial role in the perception of gender? Beginning of the answer by Théa Lefeuvre, Bertille Porcq, Chloé Lepeintre and Clara Diez, students of the DNMAde*.

Each year, the editorial staff of Unidivers joins forces with the Bréquigny high school in Rennes so that the students can approach the behind the scenes of journalism. In this context, first-year students of the DNMade – National Diploma of Crafts and Design* – offer five articles around their specialty, design. This interdisciplinary Letters & Design was initiated by the Literature teacher, Tifenn Gargam, with the collaboration of Laurent Alonzo, both teachers in DNMADe.

By definition, design is a discipline that seeks to create new objects or environments that are both aesthetic and adapted to their functions. Rather, we are talking about various design practices because, like any mode of production, it covers several areas, and is thus available in different fields: space design, product design, fashion design, graphic design, etc.

In the first sense of the term, gender designates a set of beings or things with common characteristics. But, in its sociological, psychological and cultural meaning, the word corresponds to the non-biological differences between the two sexes, that is to their social construction. It manifests itself in the way of being, of dressing and of expressing oneself of an individual.

As graphic design students, thinking about this relationship between gender and design seemed essential to us, because the latter constitutes today a strong marketing strategy, the objective of which is to attract the customer according to what he likes, often relying on his gender identity. In a society in constant evolution with respect to this sociological concept of gender, studying this discipline from this precise angle is interesting and useful.

Design and gender stereotypes from 1950 to today

“In our society, images are everywhere. We live in an era where information saturates our eyes. Their repetition often leaves a message engraved in our unconscious. These images that we see on the web, in our books, or in advertisements help us build our social identity. They show us what is expected of us in terms of behavior (as consumers, but also our way of acting in public and private)”, explains Joanne Abadie in her thesis entitled Conception du non-gender; editorial design and neutrality. The graphic designer exposes here the fact that design greatly influences our behavior and our personality, among other things, on our gender identity.

As the different practices of design began, during the 20th century, to be recognized as such and to develop, certain visions of the feminine and masculine genders were transmitted. How has design been able to establish and perpetuate many gender stereotypes?

In relation to the notion of gender, this term designates all the arbitrary characteristics, based on preconceived ideas that are attributed to a group of people according to their sex. For Jacques-Philippe Leyens, a recognized doctor in psychology, stereotypes are defined as "implicit theories of personality that all members of a group share about all the members of another group or their own ". It was the American Walter Lippmann who was the first to use this word in his book Public Opinion, in 1922, when he sought to describe fixed social representations, "pictures in our heads" (literally "images in our heads "). Finally, from an etymological point of view, it designates the typeface and therefore refers to an object reproduced in series, always identical and discarding singularities.

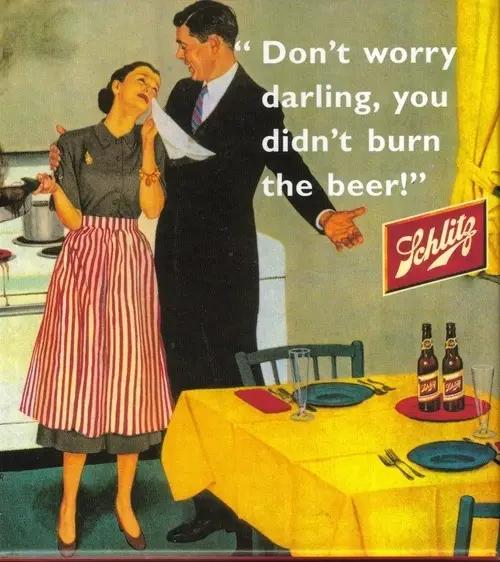

As early as the 1950s, with the appearance of a true consumer society, editorial graphics conveyed, for a long time, on advertisements, posters and magazines, a certain type of representation of women, which we would today qualify as sexist. A stereotypical portrait of the masculine gender also exists and persists as much as that of women today.

Concerning the processes used by designers whose work is imbued with stereotypes, distinguishing masculine gender and feminine gender, there is first of all typography. The latter is often fine, flexible, provided with serifs and ornaments when the message is addressed to a woman. It is mostly a round, cursive or attached font. Conversely, script typefaces, which are straighter, more formal or unstructured, are attributed to the masculine gender.

Then, we notice that the colors used in the so-called feminine design are soft, in pastel tones. There is a lot of pink and gold. Men inherit rather dark or neutral colors, such as navy blue or gray. Moreover, originally, these color assignments to the two genders were reversed. In fact, blue essentially symbolized the sky and with it, the Virgin Mary, while pink was perceived as a pale red, suited to the idea of virility relating to the male gender.

When it comes to colorful children's toys, differentiating colors based on the gender of the child is a marketing strategy. This encourages the consumer, parent of a boy and a girl, to buy a toy of each color rather than just one for both.

Magazines use these stereotypical codes a lot. For a female audience, these editorial objects generally display an animated graphic composition, and very playful, dynamic and abundant pages. The men's magazine is once again more sober, has few colors and frequently takes the form of a newspaper.

Object design is also an area where gender stereotypes manifest themselves. Here is an example: men's watches are thicker and have a rigid bracelet, to suggest the domination, the power of the man. On these types of watches, the functional and technological side of the object is often highlighted by the complexity of the design, at the level of the dial for example. As for women's watches, they are more minimalist, tapered and discreet on the wrist, in order to convey the softness and submission emanating from the stereotypical portrait of women.

In addition, Romain Delamart, in the conference "design in the genre" at ParisTech explains that the design of objects influences an unconscious collective imagery, but also on the behavior of individuals. He takes the example of the set. That of the waiter is round and can be carried in one hand. It allows fast and fluid movements and to have a free hand therefore, a greater autonomy of its gestures and displacements. That of the maid is oval and carried with the help of two large handles, which creates a sense of the tray. The woman must then adapt to this meaning. In addition, this form gives the woman a posture of submission. Thus, if a task is rather considered feminine or masculine, the design of the objects confirms this gender role in social behavior.

How design diverts stereotypes?

However, parallel to this type of stereotyped design, there is developing within this discipline, as in the artistic milieu in general, a desire to overturn codes. A change of vision which can be explained by the significant increase in the number of girls in art schools between 1980-1995, more numerous than boys from the 80s. This new generation of artists tries to raise awareness of the great public through landmark exhibitions, such as the one held in Paris in 2012, C'est pas mon genre!. The exhibits highlighted, in a questioning or more provocative way, the impact of design on the way consumers act and think.

In the world of fashion, as early as 1966, the famous couturier Yves Saint Laurent was already creating the women's tuxedo, and the famous skirts for gentlemen, from his great collection And God created Man in 1984.

Nowadays, many designers are trying, through their creations, to break down gender stereotypes, with all types of audiences, adults and children alike. The latter unconsciously internalize many stereotypes from an early age, in particular through the type of toys, books or activities offered to them. To counter this societal phenomenon, there are games such as Barbie Foot, a diversion from the traditional Baby Foot, where the players, all male, are replaced by dolls. In terms of children's literature, we can mention the collection Neither dolls nor super-heroes by Delphine Beauvois and Claire Cantais, and the albums Girls can do it too and Boys can do it too by Sophie Gourion.

We also see some advertising campaigns focus on overturning gender stereotypes. Adidas, for example, presents during its campaign, high-level sportswomen declaiming messages such as “I trace my own path” or “We create our own rules! ". For this process, the brand wanted to praise a strong woman asserting herself in an environment cataloged as masculine, abolishing gender stereotypes on this subject. We also observe a change in morals on the side of the Always and Ax brands.

Finally, there are magazines intended to shatter preconceived ideas about gender; this is the case of Fantastic Man and The Gentlewoman. These two magazines are still aimed at a particular genre category, but without using stereotypical conventional codes, quite the contrary. On the one hand, The Gentlewoman, rather intended to entertain a female audience, uses graphics in neutral colors (beige, gray) and bright blue hues. The photographs are in black and white, which brings a universal character to the magazine, and the layout of the magazine is sober.

Fantastic Man, assigned a priori to a male readership, is a magazine that aims to be minimalist, both in the layout and in the colors used. The text is generally in black, only the photographs bring color, in bright shades.

A design that ignores all gender identity?

Nevertheless, all these new communication media designed to eliminate stereotypes are not universal. Indeed, they do not meet the expectations of an audience that does not identify with either the female gender or the male gender. This is why design can exist in a completely neutral dimension with respect to this notion of gender. Graphic designer Joanne Abadie, still in her thesis Conception du non-genre: editorial design and neutrality, talks about creating a new form of non-gendered publishing, where every human being can “recognize and identify with themselves”. She wants to see this track explored “in the form of experimentation and reflection around an application to children’s publishing. »

The same year, Marie Valentine published her research article “Sex, gender and design”, where we can see her conception of a personae, representing the potential non-gendered client. The designer wondered about "the relevance of identifying our users with a sex or a gender" when developing a product: "Will this information be decisive in the use of my product or of my department? ". She illustrates her reasoning in the form of a diagram and explains that if the answer to this question is negative, then it is preferable to create a neutral product, not being intended for a particular gender category. The personae can therefore be given a neutral first name – Camille, Charlie or Dominique, be represented in the form of a non-gendered character, described in an inclusive manner and without pronouns. According to her, “(…) one of the keys to our business is to consider our users in their particularities”, without however categorizing.

On the fashion design side, many big brands like Gucci, Givenchy, Balenciaga or Louis Vuitton have launched their genderless collection. You can also find something to wear without having to choose between the men's or women's department at Asos, H&M and Zara. The Calvin Klein brand offers its unisex perfume CK One, subsequently imitated by Guerlain, Bulgari, Hermès and Thierry Mugler. The Sam Farmer or The Ordinary cosmetics ranges are also completely neutral, the first still colorful, the other more sober.

Finally, neutral design aims to highlight the functionality of the object and not the genre, or go back to the basics of the discipline. Although it displays a certain style or a particular aesthetic, it remains open to the widest consumer, without the latter being categorized as feminine or masculine. Thus, neutral design should perhaps be considered as the design of the future by everyone…

Sources / References:

http://faispasgenre.fr/2019/01/28/regne-de-binarite-genres-sacheve-monde-de-mode/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261350345_Girls_will_be_girls_a_study_into_differences_in_game_design_preferences_across_gender_and_player_types

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310616167_The_effects_of_objectification_on_stereotypical_perception_and_attractiveness_of_women_and_men

https://www.mumok.at/en/events/gender-check

https://www.cairn.info/revue-le-french-today-2016-2-page-45.htm

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310616167_The_effects_of_objectification_on_stereotypical_perception_and_attractiveness_of_women_and_men

https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/85284

Blue for girls, pink for boys

Not my style!

* The DNMADE, free public training equivalent to a bachelor's degree, prepared over 3 years, trains students in the profession of graphic designer.

The course: editorial designEditorial design consists of organizing texts and images for media that can be printed (book, magazine, billboard, etc.) or digital (website, mobile application, digital display, etc.). The editorial course aims to train generalist designers capable of designing both visual identities and information architectures for a plurality of media.

The course: identity design. The student is trained to design the visual identity of a sponsor: cultural institution, private company, brand, event, product or person. This identity will be based on selected graphic elements (typography, signs, colors, etc.) as well as on the animation of these elements. The student may be required to produce a variety of media, for the Web or television broadcasting: animated logos, trailers, commercials, television packaging, animated posters, etc.