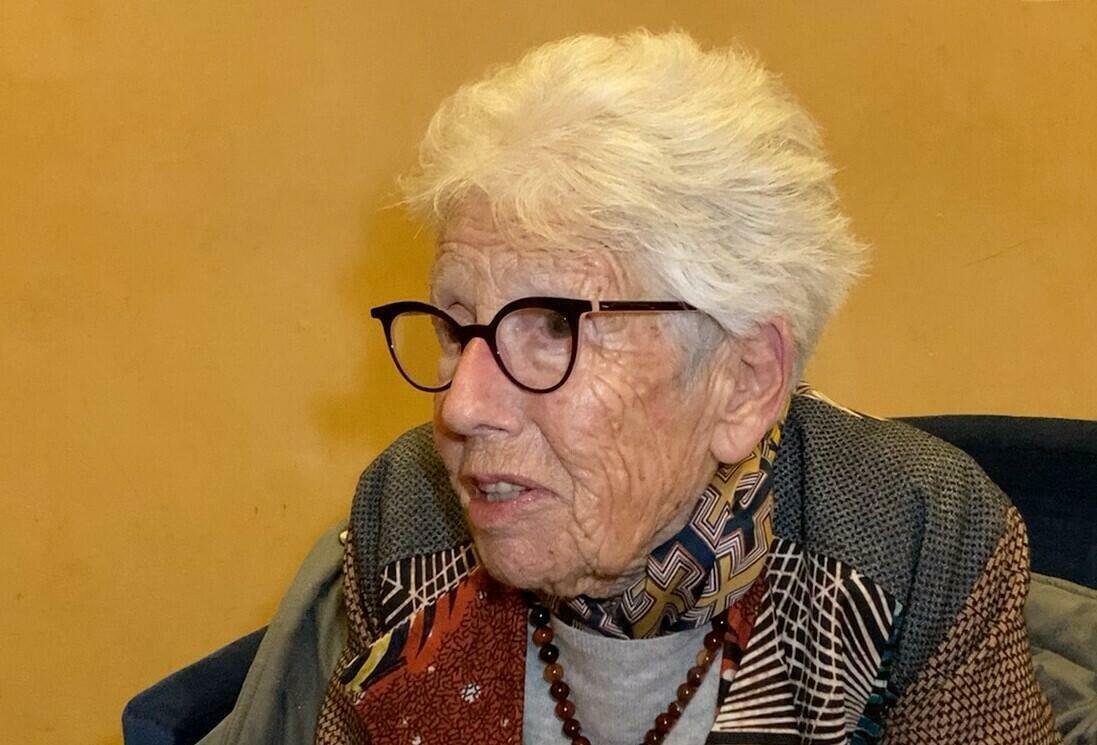

Marie-José Tubiana, specialist in Darfur and support for asylum seekers, celebrated at Fipadoc

To be recognized, each asylum seeker in France must prove where they come from. But what to do when the place of birth disappeared after the massacre? Over the past 10 years, after being rejected by Ofpra (French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons), 327 asylum seekers from Darfur have contacted Marie-José Tubiana. This great Darfur expert will search for days and entire nights for the name of a disappeared village on old maps.

In 20 years, civil war and genocide have left more than 300,000 dead and three million displaced in Darfur. Inhabited by a real mission, Marie-José Tubiana, former director of research at the CNRS, mobilizes her knowledge of the field, acquired over 60 years, to prove the veracity of the stories of the refugees and to have them respected.

Interview between ethnologist Marie-José Tubiana and Camille Ponsin, director of the film "Marie-José is waiting for you at 4 p.m.", awarded this weekend at Fipadoc.

RFI: Your story with the refugees from Darfur does not begin either in Sudan or with your film Marie-José is waiting for you at 4 p.m., but in the jungle of Calais.

Camille Ponsin: It started with a stay that I made in the jungle of Calais, in France, because there was a large migrant camp, settled there for many years and which really expanded significantly in 2015. I am went over there, without a camera, to see for myself what was going on there and see the situation there. First, I spent a good part of the summer of 2015 helping people there, Syrian, Afghan, Eritrean and Sudanese refugees. This is where I first met genocide survivors from Darfur. Then, I hosted one of these refugees in my home for a year. And I wanted to know more about the history of his country and about Darfur in general. It was at this time that I read books by Marie-José Tubiana. I first knew Marie-José Tubiana through her books.

RFI: And you, Marie-José Tubiana, when did your story with Darfur begin?

Marie-José Tubiana: I went to Darfur in 1965. At first I wanted to come back to Chad, but the president of Chad at the time, Tombalbaye, found that I should not work on the people of the North, but that I had to work on its population. I told him that you don't change your line of conduct like that. So, I refused. We did not have the visa and we could not leave. So we left for Darfur a few months later, very easily.

>> To (re) read: Fipadoc: "Shadow Game", the "game" of young migrants from Africa and Asia to cross borders

RFI: Your first appointment, Marie-José, you gave it at 4 p.m., hence the title. Is it a film about the fate of refugees from Darfur or a portrait of Marie-José?

Camille Ponsin: For me, it's both. It is a film about both genocide survivors and refugees from Darfur, but it is also a film about ethnologist Marie-José Tubiana and all the work she does today. I needed to tell the story of this woman who I find extraordinary. She is for me a Righteous Among the Nations [the term Righteous Among the Nations originally designates non-Jews who took risks to rescue Jews threatened by Nazism during the Second World War ed. ], a great scholar, a great ethnologist, and also a great photographer, because she took a lot of photos with her Leica during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, in Darfur. She made films in 16 mm [after having learned to manipulate the camera with the great filmmaker Jean Rouch, editor's note]. Doing the portrait of Marie-José Tubiana allowed me to tell about Darfur, to tell about the people of Darfur. And it was the best gateway, the best way to tell this country, to be able to go back in history from the 1950s, 1960s, when the country was still at peace, before there was the genocide, in 2003.

RFI: You have become a very great specialist in Darfur, a great ethnologist, you have taken magnificent photos and films. What fascinated you the most when you were there in Darfur?

Marie-José Tubiana: The welcome and the kindness of the people, the fact of being able to work in a collective. People came to work in groups. They knew we were there to make history. The important thing was to explain what we came to do with them. There was a group of people, about twenty people, who all knew part of the story. They were happy to work with us and enrich each other. The next day, they came back saying: there, I was not very up to date, but I am bringing so and so who was a witness and who can help you. It is this collective way of working that seemed very interesting to me.

RFI: You put many different layers into your film: current events, history, beauty, terror... How did you design your film?

Camille Ponsin: I first wanted us to relate to the character of Marie-José. For that, I start with a long, fairly calm sequence, at her place. I wanted her to be at the center of the film and at the center of the emotion. It is also a film about a woman and my view of this woman at work. Through the portrait of Marie-José Tubiana, I manage to talk about history. She herself is a Darfur specialist. Through his books and his writings, I had the story. I also had a sensitive testimony, a moving testimony on Darfur, which was not only scientific investigations.

She carried out scientific investigations as an anthropologist, with the rigor of anthropologists, but she also wrote much more personal, much more intimate stories, her "Dar For road diaries". It's like a logbook she was telling. We focus on the story of Marie-José, this extraordinary woman and then go down in history with a capital 'H'. The third layer was obviously the horrors and atrocities of the Darfur genocide. And then, the odyssey and the whole journey of the refugees to reach Europe by crossing Libya, the Mediterranean. All of this was brought to me by the very strong testimonies of genocide survivors.

What interested me was to weave these two stories together. The old story, Darfur in peace, an intimate, harmonious, luxuriant Darfur, with the contemporary and harsher story with the survivors of the genocide who tell me about all the dramas and all the horrors that have been committed. I wanted to combine these two stories. I wanted it to be stretched with both a silk thread and a steel thread.

RFI: For ten years now, you have been helping asylum seekers from Darfur. Why this commitment?

Marie-José Tubiana: In Darfur, it is people who practice giving and counter-gifting. For example, with respect to matrimonial compensation, the whole family contributes. Those who have contributed so that the family or the clan can acquire a wife, they will respond in turn. There is this exchange of gift and counter-gift. For me, it's the same. They gave me lots of things. They participated in many things. How, now, could I let them down? It is not possible. I, too, owe them a debt. I'd be a traitor if I didn't do that.

RFI: At the premiere of the film, you don't know that there will be a young man from Darfur in the room who will thank you. Thanks to you, he obtained the right of asylum in France. How do you feel at that time?

Marie-José Tubiana: I'm very happy. That means I got it done. This boy, I don't remember. Now I remember him. He came to my house twice. And he remembers everything very well. When he was at my house, he would say, 'We feel like we're at home. There are lots of things from ours at yours on the walls, the shelves... You have the big basket, you put things in it, you use it. So, we feel at home with you.' I am very happy that asylum seekers feel at home with me.

RFI: How new is your perspective on immigration from Darfur?

Camille Ponsin: The idea of making a film about Darfur and the refugees from Darfur had been bothering me for a long time. I wanted to offer something different, not just a moral or complacent approach. I wanted us to focus on facts, on a very precise story, to give back the story to these peoples of Darfur whose history we do not know. Behind the word migrant or refugee, we can put everyone, all refugees, but, in fact, no one is really there with their own story. With Marie-José Tubiana and her scientific, and sometimes even almost cold, approach to the facts - what happened, how it happened - it was another way of approaching this problem far from heated debates, or with too many emotions.

>> To (re) read: Côte d'Ivoire at Fipadoc: "Aya is the first avikam heroine of cinema"

RFI: In the film, there is the beauty of Darfur, thanks to your images and your stories, but, afterwards, there are also all the terrors that have occurred in Darfur. How does the film look at Darfur?

Marie-José Tubiana: I find what happened sad. And I find everything that is happening now heartbreaking. To see that we, Europe, are giving money to the Sudanese authorities so that they prevent people from crossing the Mediterranean. This money, to whom do we give it? To the people who martyred the people of Darfur. So that they put a brake on [people trying to leave]. And they willingly curb them. That is heartbreaking.

RFI: After watching this review of your work on the big screen, what do you want to pass on to future generations?

Marie-José Tubiana: I hope this will help them. I transmit a knowledge of what it was before. What it was like during the scorched earth policy. What we did was wipe things off the map, wipe people out, set them on fire, kill them, make them leave. If they can return home in peace, I think they will, maybe not all of them, but probably some. The people who have obtained asylum in France, I have tried to get them to go to the countryside for a bit. But that was utopian. They said, 'No. We no longer want to take care of animals, we want something else. We want to learn trades.' There is one, very good, who laid the carpet. I said to him: 'It may not be very useful if you go back to your country, but it doesn't matter, you live by laying the carpet. You learn things. It is their choice. And I do not intervene in their choice. I try to offer them things, but if they don't want to, they don't want to.

RFI: Marie-José is now apparently the only expert in this field. She will soon be 92 years old and also want to stop one day. How can this aid be sustained?

Camille Ponsin: This is the question that worries us all, because the fate of many young men and women in Darfur depends on these certificates. It changes their life to have this political refugee status or not. If they do not have it, some are deported to Sudan, others are condemned to live without papers, therefore in very difficult conditions. What are people going to do if Marie-José Tubiana can no longer help them? What will happen is that she will first transmit her personal documentation, because she is the only one to have such documentation. There are very few other people in France who can help refugees from Darfur to prove things. And no one has his knowledge, his knowledge and, above all, all his personal archives. She herself made geographical surveys, geographical maps in 1965. At the Ofpra, they don't have the maps and tell the refugees: 'Your village no longer exists, we can't see it on the map' . Marie-José can bring out her cards. All this documentation and these personal archives will be archived, classified, so that others can use them to help the survivors of the genocide.

The difficulty is that it is a job that requires a lot of time. Marie-José has devoted all her time to it for about ten years. His son, a journalist and researcher, took up the torch a bit. He is investigating in Darfur today. He also sometimes does this work with refugees, but he obviously has much less time than Marie-José to devote to it.

So, I hope that when the film comes out in October, people will come forward: lawyers who will come to her to take stock with her. Perhaps there will be someone, among the young ethnologists and anthropologists, who will take hold of this question and of the documentation and archives of Marie-José, in order to be able to continue her work.